Authors:

Published:

There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to web archiving techniques, and the variety of tools and services available to capture web content illustrate the wide, ever-growing set of needs in the web archiving community. As these needs evolve, so do the web and the underlying challenges and opportunities that capturing it presents. Our decade of experience running Perma.cc has given our team a vantage point to identify emerging challenges in witnessing the web that we believe extend well beyond our core mission of preserving citations in the legal record. In an effort to expand the utility of our own service and contribute to the wider array of core tools in the web archiving community, we’ve been working on a handful of Perma Tools.

In this blog post, we’ll go over the driving principles and architectural decisions we’ve made while designing the first major release from this series: Scoop, a high-fidelity, browser-based, single-page web archiving capture engine for witnessing the web. As with many of these tools, Scoop is built for general use but represents our particular stance, cultivated while working with legal scholars, US courts, and journalists to preserve their citations. Namely, we prioritize their needs for specificity, accuracy, and security. These are qualities we believe are important to a wide range of people interested in standing up their own web archiving system. As such, Scoop is an open-source project which can be deployed as a standalone building block, hopefully lowering a barrier to entry for web archiving.

Witnessing the web is hard

How does one go about capturing a slice of the web as accurately as possible and attest that what was captured is what actually “happened”? In most cases, answers to that question revolve around the level of trust that users put in the institution that is responsible for capturing and hosting web archives, and on a shared understanding of the way that the underlying capture technology works. For example, users trust captures made by the Wayback Machine because it is operated by the Internet Archive, a known and trusted organization that is transparent about its collection process. Our very own Perma.cc operates in a similar way.

While this centralized trust model helped shape the way we think about web archives, it suffers from two main limitations that can sometimes hinder its ability to accurately witness the web:

- The first is technical: because a centralized entity is responsible for both capturing and storing archives, the same policies and constraints apply to every capture. While these rules are generally enforced for legal or technical reasons, not being able to adjust them may pose fidelity challenges that can weaken the intrinsic value of the resulting web archive artifacts. An example of this phenomenon can be seen in the temporal violations that are sometimes present in Wayback Machine playbacks, or in Perma.cc’s hard cut-off of captures after 200MB of data collected (a cap that was raised from 100MB in 2019 specifically to help capture large documents in relation to then-President Trump’s first impeachment trial).

- The second is conceptual: because trust comes solely from the institution, it evaporates as soon as the web archive file leaves its platform of origin, or if said platform disappears: how can a loose WARC file be trusted?

It is with that problem space in mind that we’ve created Scoop.

No-alteration principle

The “no-alteration principle” is a core component of Scoop’s architecture, and has been a guiding thread throughout its development. In essence, we hypothesize that HTTP exchanges should be recorded “as is” and that any intentional alterations to those exchanges may reduce the intrinsic value of the resulting capture for the use case of being reliable witnesses of the web. But how exactly does this translate into an actual software architecture and capture technique?

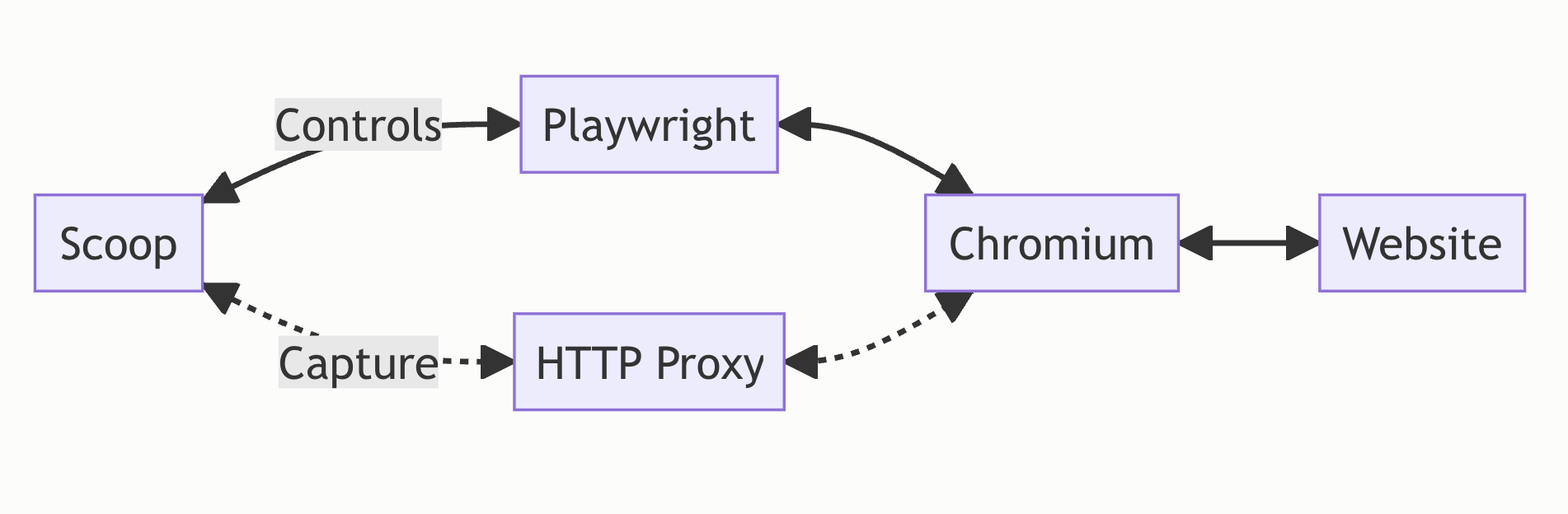

Scoop is a browser-based capture engine which uses Playwright to “pilot” an instance of the Chromium browser to reach a URL. To capture data, it uses a custom HTTP proxy to intercept network exchanges happening between Chromium and the server hosting the web page. The granular control we have over the HTTP proxy gives us a certain confidence that what we intercepted was indeed what the server sent to the browser, unprocessed, including elements of forensic relevance that would have otherwise been discarded, such as broken or duplicate HTTP headers.

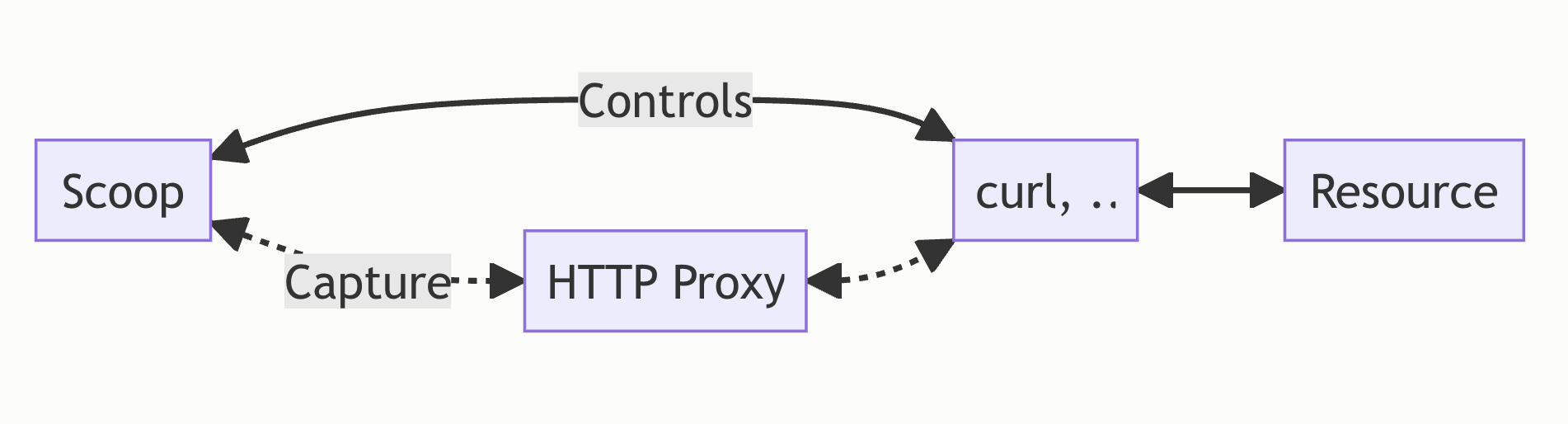

Scoop can also capture resources served over HTTP that are not web pages, such as PDFs. In that case, while it may use curl (for example) instead of a web browser to access the resource, it still uses the same custom HTTP proxy to intercept exchanges.

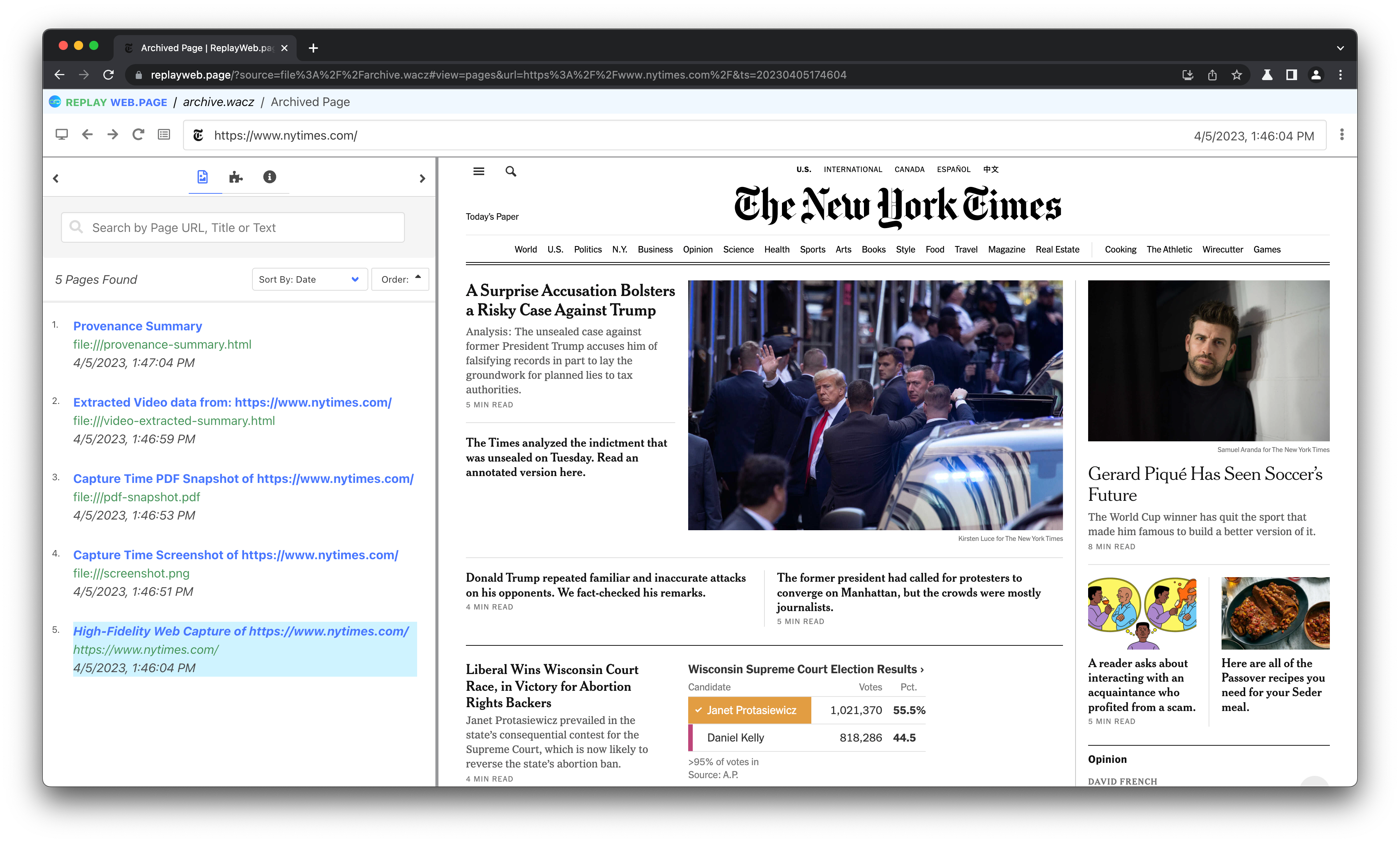

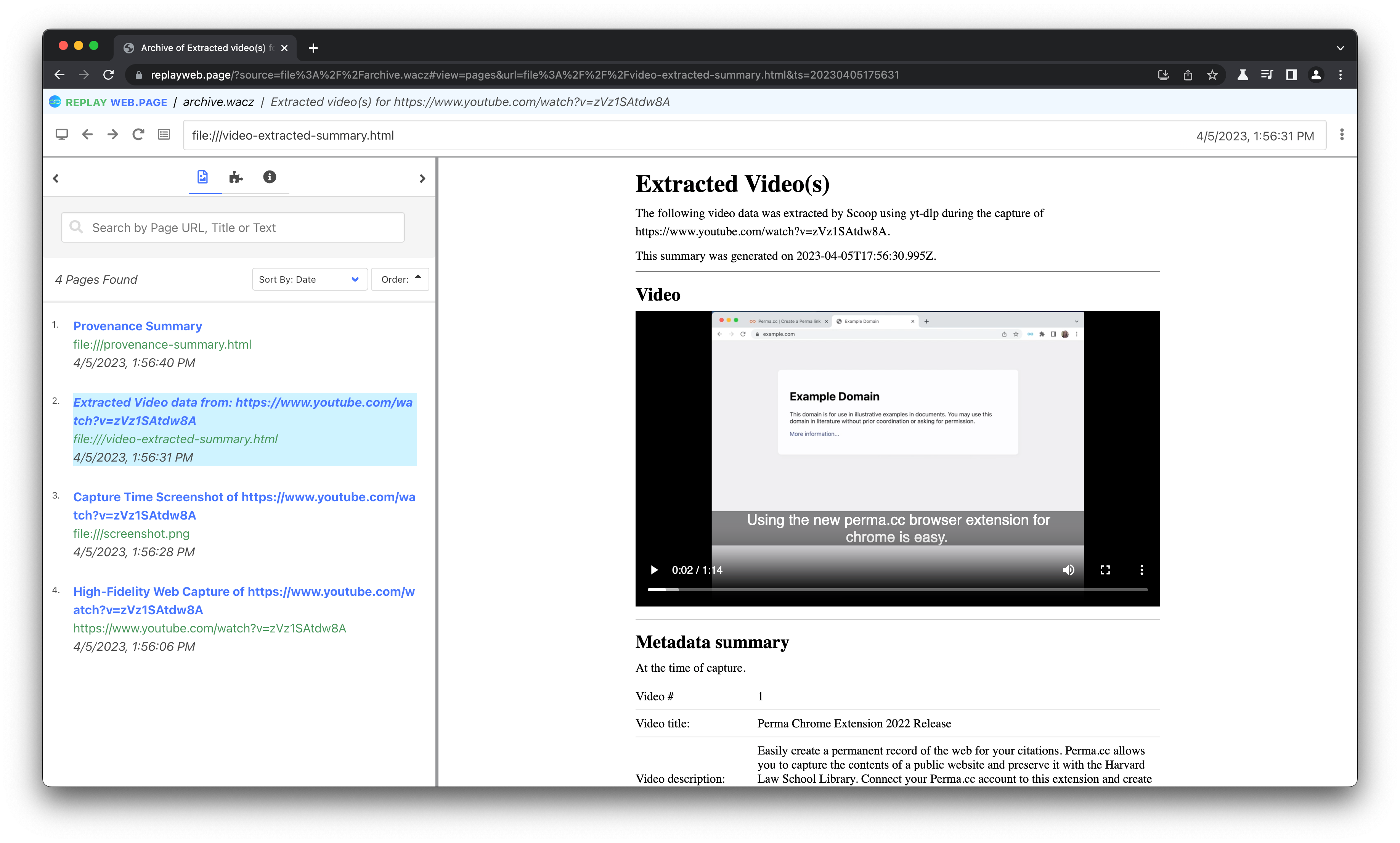

Importantly, Scoop makes a clear distinction between the “principal” capture, which is what was intercepted while browsing the requested resource, and what we call “attachments”. The latter concept allows us to preserve elements and contextual information that cannot necessarily be caught via network interception, without making alterations to the capture itself. A good illustration of this is the “capture video(s) as attachments” feature, which allows for capturing “out of band” videos that may be present on a page. This feature may prove useful to capture rich media that are embedded in custom players with discrete network behaviors, which would otherwise be difficult to either capture or play back without significant rewriting.

High fidelity requires fine tuning

We would very much like for Scoop to empower people to run their own web archiving systems. As such, we believe it is important that the tool itself does not make policy decisions for its users but, instead, allows them to craft their own capture policies—the idea that everything should be customizable unless it infringes on the no-alteration principle is central to Scoop’s design.

For this reason, everything aside from the core capture is both optional and configurable. Every attachment (screenshot, PDF snapshot, videos as attachments, …) is optional and every part of the capture process can be constrained and tweaked (time and size limits allowing for “partial” captures, URL block listing …). Scoop comes with sensible defaults for all these options, which can be edited individually. Scoop also allows for customizing the way the browser interacts with web pages; it integrates Webrecorder’s browsertrix-behaviors for automating such interactions, all of which can be selectively turned on or off.

Built-in provenance and authenticity assertion mechanisms

Decentralizing the process of web archiving cannot be fully achieved without a decentralization of trust, which requires both the embedding of strong provenance information in each web archive file and authenticity assertion mechanisms by which to verify that information. Scoop approaches these challenges from a few different perspectives.

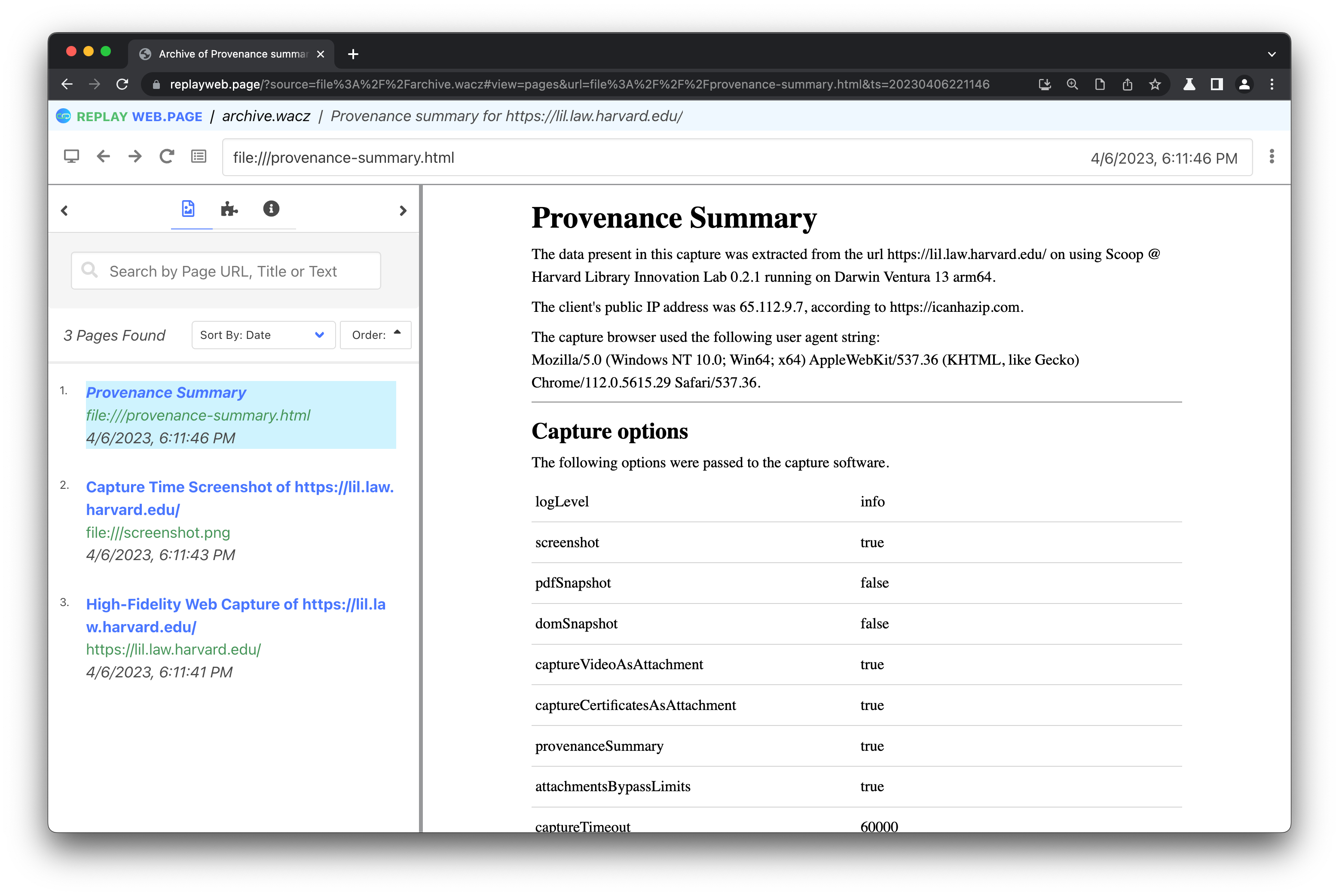

The first is the provenance summary feature, an optional attachment that condenses information about “what happened” during capture, such as which configuration options were passed to Scoop, details about the system and network it was run on, and the URLs that were intercepted by the blocklist.

In addition to this provenance summary, Scoop can also preserve, as attachments, the different SSL certificates that were encountered during capture—a piece of information that may be crucial to confirm the “identity” of the web page that was captured.

Finally, Scoop comes with built-in support for the Web Archive Collection Zipped (WACZ) file format, an emerging standard initiated by Webrecorder, and for the WACZ Signing and Verification specification that the Library Innovation Lab helped design. Specifically, it supports communicating with an authsign-compatible server to apply a cryptographic signature to a given WACZ file, using an X509 certificate, allowing the archivist to “seal and stamp” it. Once signed, the file cannot be altered without breaking that seal and, depending on the nature of the certificate that was used to sign it, its origin may be traced back.

Navigating trade-offs and building for the future

While Scoop is already a stable library, we acknowledge that some of the decisions we’ve made in designing it may need to be revisited in the future, whether because of changes in the underlying challenges involved in witnessing the web or simply because we will be proven wrong on some of the calls we’ve made. We have taken steps to facilitate the implementation of these future revisions and experimented with ways of augmenting captures made with Scoop, today, with features that will be implemented tomorrow.

For that latter point specifically, we’ve created an export format which we call “WACZ with raw exchanges” which consists of a valid WACZ file that includes all the exchanges that the proxy intercepted in raw form as individual text files.

This allows for future-proofing these web archive files in two ways:

- These raw exchanges may contain data that could not be saved as part of the underlying WARC file because of current formatting constraints. In that specific case, keeping a copy of RAW exchanges allows for preserving information that would otherwise be lost.

- Importantly, Scoop supports “ingesting” WACZ files containing raw exchanges for later re-processing, allowing existing captures to potentially benefit from software updates.

Using Scoop today

On our end, we plan to replace Perma.cc’s capture engine with Scoop, which we expect to both improve the experience of Perma.cc’s users and help improve Scoop.

We are thinking of Scoop as both a feature-complete end product and a building block. While one can easily install it on a machine and use it directly via the command line to capture web pages — a use case we want to facilitate as much as possible — Scoop was also designed to be consumed as a software library. As such, it comes with a JavaScript API for Node.js which we hope will make it easy to integrate into larger web archiving systems. Supporting both ends of that software use case spectrum required being mindful of both resource consumption and dependencies management. For it to be both portable and production ready, regardless of its environment, we needed it to be nimble and self-contained. We hope that seeing Scoop deployed in unexpected contexts will help us refine its architecture further.

We cannot wait to see what the community builds with Scoop and very much welcome feedback and contributions, especially at the project’s official GitHub repository page: https://github.com/harvard-lil/scoop.

Scoop was designed and developed by Matteo Cargnelutti and Greg Leppert, with the help of their colleagues Clare Stanton, Ben Steinberg, Rebecca Cremona, Jack Cushman, and with the support of the entire team at the Harvard Library Innovation Lab.

We are grateful to Ilya Kreymer and the Webrecorder project for inventing and popularizing many of the formats, technologies, and insights behind Scoop, and for being a sounding board and thought partner throughout the history of Perma.cc.